leeds-live.co.uk

Memorials to David on Leeds Bridge have twice been torn down hours after their installation

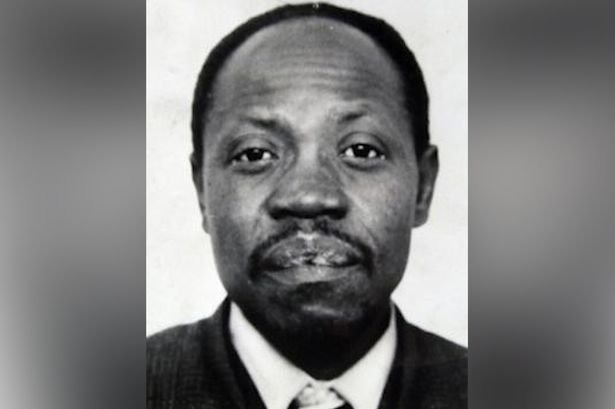

David Oluwale’s death in 1969 led to the first prosecution of British police for involvement in the death of a black person

A blue plaque commemorating the heartbreaking death of David Oluwale was stolen hours after it was installed on Leeds Bridge in act police are treating as a hate crime.

A temporary memorial to David was taped in its place. A few hours later it was vandalized.

You’d think by this swift, a brutal response that David was a controversial figure, like say, slaver Edward Colston. David Oluwale was not.

David was a controversial figure, like say, slaver Edward Colston. David Oluwale was not.

He was a poor Nigerian immigrant looking for a better life in “The Motherland” of Britain which he had learned to revere at school. Instead, he suffered unimaginable discrimination and abuse before he was “hounded to death” by racist police officers protected by a prejudiced justice system. Here is David’s story.

David Oluwale was born in Lagos, then the capital of Nigeria, around 1930. His father, who worked in the fishing trade, died when David was around seven years old.

Aged about 19, he stowed away on the SS Temple Bar, a cargo ship bound for Hull. Work in Lagos was scarce – David earned a few pence collecting golf balls at a colonial golf course, according to a friend – and could not afford the fare.

Smoked out of his hiding place amid boxes of groundnuts, David was handed to the authorities when the ship docked in Hull. He was jailed for 28 days as a stowaway under the Merchant Shipping Act but as a citizen of the British Empire, he was allowed to stay in Britain.

He served his time at Armley Prison and Northallerton Prison before heading to Leeds. David had trained as a tailor in Lagos and believed he would find work in the city.

David did find jobs and places to live in Leeds although neither lasted long. Racial discrimination in 1950s Leeds closed many doors to him. Some of his former colleagues said David, nicknamed “Yankee” for his love of westerns, could be stubborn and insubordinate which didn’t help in a Britain then heavily weighted against Black people.

He did, however, make friends with a few West Africans living in Leeds at the time. One described him as “a quiet man” and “always happy and smiling”. Another said he was a “good conversationalist… always making jokes and could be the life of the party”.

But three years later, David would enter a horrible spiral of poverty, crime, severe mental illness, and abuse. In 1953, he was jailed for assaulting a police officer and damaging a police uniform following a row over a bill at the King Edward Hotel. Friends, however, said the policeman hit David with his truncheon which may have caused permanent brain damage.

Back in Armley Prison, a medical officer observed David acting strangely. He was taken to St James’s where he was described as “loud, excitable and terrified”. David was sectioned and transferred to the city’s infamous High Royds psychiatric hospital in Menston.

David was detained at High Royds and sedated using chlorpromazine, known as a “liquid cosh”. He was released from High Royds in 1961 having never received a single visitor.

Institutionalised and damaged by his time at High Royds, David found a job and somewhere to live but it was short-lived. His friends described him at the time as “nervous, twitchy, slow, shuffling [and] laughing for no reason”.

He drifted between London and Sheffield but always returned to Leeds. Unemployed, David became homeless and in 1965 he was charged with assaulting two policemen who caught him entering a derelict house where he had previously slept.

Back again in Armley Prison on remand, a prison psychiatrist found David “very paranoid about the police whom he accused of ill-treating him, stealing his money and persecuting him”.

He was sent back to High Royds in November 1965 where he remained until April 1967. David returned to Leeds where he lived on the streets around Kirkgate Market and occasionally in hostels. Discrimination at the time meant David and other Black men were barred from such places

It was thought to have been around April 1968 when David first encountered Sgt Kenneth Kitching and Insp Geoffrey Ellerker, two Leeds policemen who would systematically make his already miserable life a living hell.

According to accounts, the officers would grab David from the street in the middle of the night – another policeman saw Kitching urinating on David as he lay in a shop doorway– and take him to Millgarth police station for a beating. On one occasion, Ellerker kicked David in the groin so hard his body lifted from the floor, one witness said.

The officers would, according to accounts, make David do what they called “penance” forcing him to kneel before them and kicking away his arms causing his head to smash into the pavement. Sometimes they would drive him miles from the city centre and abandon him hoping he would leave Leeds – but he always returned because it was his home. Having dumped David in Middleton Woods at 3.30 am, the officers are said to have joked David would “feel at home in the jungle”.

The last time David was seen alive was probably on April 18, 1969, when a bus conductor saw a short (David was 5ft 5in), scruffy man being chased by two police officers down an alley close to Leeds Bridge. He was screaming and clutching his head. David had earlier been beaten with truncheons in the doorway of John Peters Furniture store, Lands Lane.

Another witness, a local petty criminal, said he had seen two policemen beat a small, “dark man” unconscious and kick him into the river. David’s bruised body was found 2.5 miles downstream, near Knostrop Weir, 16 days later. He was buried in a flimsy coffin, stuffed with old phone directories, in a pauper’s grave with nine other people at Killingbeck Cemetery. The service was attended only by Fr Martin Carroll from St Anne’s Cathedral, undertakers, and gravediggers.

An inquest recorded David had drowned and there were no suspicious circumstances. Leeds police officers closed ranks and for Kitching and Ellerker, they probably believed it was over.

But a scrupulous police cadet, Gary Galvin suspected Kitching and Ellerker were behind David’s death. Rumours of David’s beatings were flying around Millgarth around the time Ellerker was sacked and jailed for covering up the death of Minnie Wein. The 69-year-old was hit and killed by the drunk driver of an unmarked police car – alleged to be Supt Derek Holmes – on a pedestrian crossing near the Skyrack pub in Headingley.

Scotland Yard launched an inquiry into David’s death and Kitching and Ellerker was charged with manslaughter, perjury, and GBH. But British justice wasn’t exactly blind when the pair came to trial.

Racist terms were found on police paperwork relating to David yet racism was never mentioned during the trial. Witness statements that didn’t fit the negative image of David as portrayed in court were excluded from the trial. Indeed, judge, Mr. Justice Hinchliffe said during the trial: “It is accepted on all hands that [Oluwale] was “a dirty, filthy, violent vagrant”.

The judge directed the jury at Leeds Assizes Court to acquit Kitching and Ellerker of manslaughter although the pair were found guilty of his assault. Ellerker was jailed for three years while Kitching received 27 months.

Justice was not served but it was the first successful prosecution of British police officers for involvement in the death of a Black person. David’s unimaginable, unmerited suffering caused a public outcry but the case faded from the public sphere until 2007 when police paperwork detailing the case was declassified under the 30-year rule.

The case exposed some of the most appalling racism, brutality, and corruption in British policing as well as an institutionally prejudiced justice system.

Books, plays, a charity dedicated to David’s memory, and hopefully a new plaque on Leeds Bridge will ensure neither he nor the injustice he suffered is forgotten again.