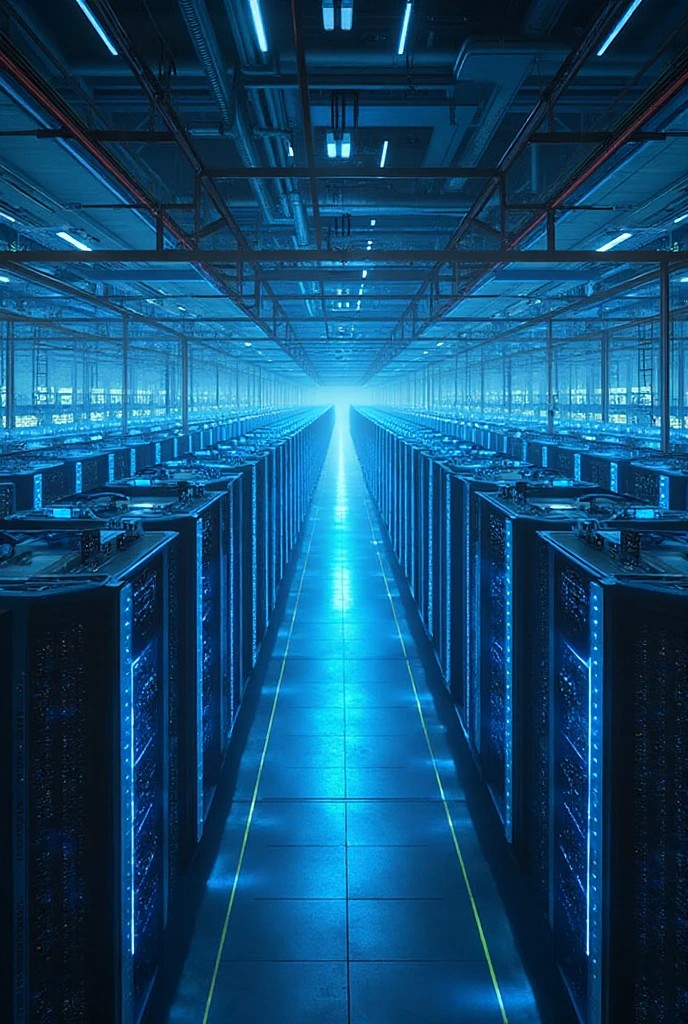

Across the globe, a quiet transformation is underway. Venture capital flows into artificial intelligence startups at unprecedented speed, data centers rise like new cathedrals of power, and governments debate how to regulate something that seems to evolve faster than they can legislate. Artificial intelligence is no longer a curiosity tucked into research labs. It is becoming infrastructure, woven into education, medicine, finance, law, media, and even the creative arts. The optimism around efficiency is overwhelming: machines that do not sleep, do not demand benefits, do not quit, and do not get distracted. For companies, this looks like the end of frustration with human limitations. For society, however, it opens a fundamental dilemma. If machines can take on so much, will there still be enough jobs left for people?

This question has echoes in the past. Every industrial revolution has carried with it a wave of fear that machines would permanently destroy human livelihoods. When the spinning jenny and the power loom arrived, textile workers rioted, smashing the new devices they believed were robbing them of bread. Steam engines replaced field labor, and in the nineteenth century many feared that mechanized farming would throw millions into unemployment. In the twentieth century, computers automated bookkeeping, factory production, and communication. Each time, the direst predictions did not come true. New industries eventually grew out of the upheaval, providing jobs that had not existed before. Railroads needed engineers and conductors. Factories needed managers, designers, and accountants. The information age produced coders, digital marketers, and IT specialists. The pattern has been remarkably consistent: disruption wipes out one set of jobs but, over time, another set emerges.

Yet the pattern is not a guarantee. Each transition was marked by years of hardship for workers caught between what was destroyed and what had not yet been created. Even today, the communities that once relied on coal mining or steel production are still struggling to find their footing in economies dominated by knowledge work and services. The transition costs were real, and they lasted decades. The same may prove true in the AI revolution, but the stakes are higher because of the nature of the work being displaced.

Artificial intelligence is not just another machine that handles physical labor. It is a machine that operates in the realm of thought itself. It can write essays, compose music, generate art, review contracts, diagnose diseases, tutor students, design marketing campaigns, and even suggest scientific hypotheses. The arrival of AI challenges the assumption that there are zones of human activity machines cannot cross. If steam was the replacement for muscle and electricity the replacement for repetitive processes, then AI is the replacement for many forms of thinking. That strikes at the very heart of what people believed would always set them apart.

If the old equation was simple: machines destroy physical jobs, new industries create intellectual ones, the new equation is far less reassuring. AI is able to replicate both. It is already working alongside doctors, journalists, teachers, and designers. It does not mean the end of those professions tomorrow, but it does mean that the ceiling of what machines can do has risen dramatically. That expansion makes it harder to imagine a neat balance between old jobs lost and new jobs found.

The real determinant, however, will not be the machines themselves but the societies that use them. Different cultures and political systems interpret efficiency and human value in strikingly different ways. In some countries, the dominant idea is that the market must decide. If a machine can perform a role cheaper and faster, then the machine should win, and people must adapt. In this environment, efficiency is the highest virtue, and jobs vanish quickly. In other societies, there is more hesitation. Governments or cultural codes intervene to slow the pace, to retrain workers, or to provide safety nets that soften the blow of transition. In these contexts, efficiency is balanced against stability, and even against dignity.

The United States offers an example of the first approach. It has always embraced disruption as the cost of innovation. Workers who lose jobs are expected to find new ones, and while this creates enormous dynamism, it also produces waves of inequality and insecurity. By contrast, Scandinavian countries have a tradition of cushioning disruption with generous welfare systems, high taxes, and policies that insist on shared benefits from technological growth. They do not reject innovation, but they insist on distributing its rewards. Japan provides another model, where companies often retrain workers rather than dismiss them outright, reflecting a cultural emphasis on loyalty and group cohesion. China demonstrates yet another pathway, one where the state pushes AI adoption aggressively to gain global power, but also steers the direction of its development to serve national objectives.

The choice of pathway has direct consequences for whether jobs will remain accessible. In a society where efficiency is absolute, many human roles may vanish without replacement, at least in the short term. Cheaper services do not help someone with no income at all. In a society that insists on human inclusion, work may be deliberately structured to keep people engaged, even if the machine could do the job more easily. That may seem inefficient in a narrow sense, but it reflects a decision that participation is more important than raw productivity.

This tension reveals an uncomfortable truth. The future of jobs is not dictated solely by technology. It is also shaped by values. A company that chooses a machine over a human is not just making a cost calculation, it is expressing a vision of what kind of economy it believes in. A government that retrains its citizens rather than discarding them is not just delaying the inevitable, it is declaring that belonging matters as much as efficiency. The machines are the same in every country. What differs is the way people choose to live with them.

So will there be enough jobs to go around? There will always be work to do. The question is whether that work will be paid, dignified, and shared widely enough to sustain communities. If society prizes only speed and profit, then many will be excluded. If society insists on participation, then work will continue to exist, even if in transformed forms. The future is not written in silicon or code. It is written in the choices humans make.

Author: Michael Abioye

Lagos, Nigeria

Senior Writer